Opening the Doors of Conservation to Everyone with Maps

Breece Robertson, Center for Geospatial Solutions at the Lincoln Institute of Land PolicyEvery minute, we lose the opportunity to protect the most unique and important places in our landscapes and communities due to unprecedented human pressures. Once lost, most of these places can never be converted back to their natural state or integrated into a protected, connected system. It’s not just the land we lose, we lose our connection to nature and to each other. These connections are critical to our individual and collective health and wellbeing, and to that of the planet. We lose habitat that supports the survival of species. We lose opportunities to provide communities with equitable access to parks and open space. We lose natural buffers and features that protect vulnerable communities from climate events.

Bold visions like E.O. Wilson’s Half Earth Project and the United States’ America the Beautiful Initiative set forth that we need to protect a minimal percentage of land to survive and thrive. But we must act fast and scale our conservation efforts to meet the challenge. The year is 2021; 2030 is not far away. Consider that in the Western United States, we are losing open space to human development at an alarming rate— the equivalent of one football field every two and a half minutes and an area larger than Los Angeles each year (Center for American Progress). There is no time to waste.

The good news is that we have sophisticated and powerful geospatial data, tools, applications, science, and the will of our communities to do smart conservation planning, storytelling, and management. Data combined with community and partner-driven approaches helps guide the urgent actions needed to protect special places that are in danger of being lost forever. Maps help us understand where to focus restoration efforts to improve and manage lands for resilience and adaptation. These data and tools are not out of reach. Whether you are a GIS professional, a CEO, an Executive, a board member, a conservation professional, or an activated citizen, you can tap into the power of GIS to guide and implement strategic conservation and park system planning for mission critical impacts. GIS is more accessible than ever with modern online web mapping and application tools that support even the novice to create maps and apps in minutes.

Photo by Felipe Rodriguez

We have immense untapped potential to accelerate land protection and we can’t afford not to use GIS to support this effort. Data and geospatial technologies show us what to protect and provide tools to monitor and effectively manage those places. This information helps us advocate for funding and policies that improve water quality, build highway over- or under-passes for wildlife connectivity, plant trees to keep streams cool for fish and reduce evaporation, create resources for low-income neighborhoods for resilience, and protect coastlines to defend against sea level rise and storm surge.

In my new book, Protecting the Places We Love, Conservation Strategies for Entrusted Lands and Parks, I describe the powerful ways that GIS can not only support an organization or initiative – but drive vision, innovation and impacts across partnerships and landscapes. The book is a call to action for organizations big and small to use GIS to come together to address our most pressing issues of biodiversity loss, park and open space equity, and climate change—and no other network of practitioners are better poised to work across scales and boundaries than those working on landscape connectivity and conservation.

My goal in writing this book was to show that no matter what your capacity, budget, or staffing, we can all access geospatial data and tools today, and that a lot of the perceived and real barriers to GIS can be overcome. Chapters cover topics ranging from storytelling with maps, mapping equity, biodiversity, connectivity and climate resilience, large landscape conservation, community engagement strategies, strategic conservation planning, policy and advocacy, and more. In each chapter, many of these questions will be explored:

- What is the challenge, need or vision that GIS can help address or accomplish?

- How to create support for your project or endeavor?

- How do you approach the challenge?

- Where do you get the data?

- What are the methods to map, model and analyze the issue?

- How do you translate the results into action or recommendations?

- How are the results valuable and why are the outcomes different because of GIS?

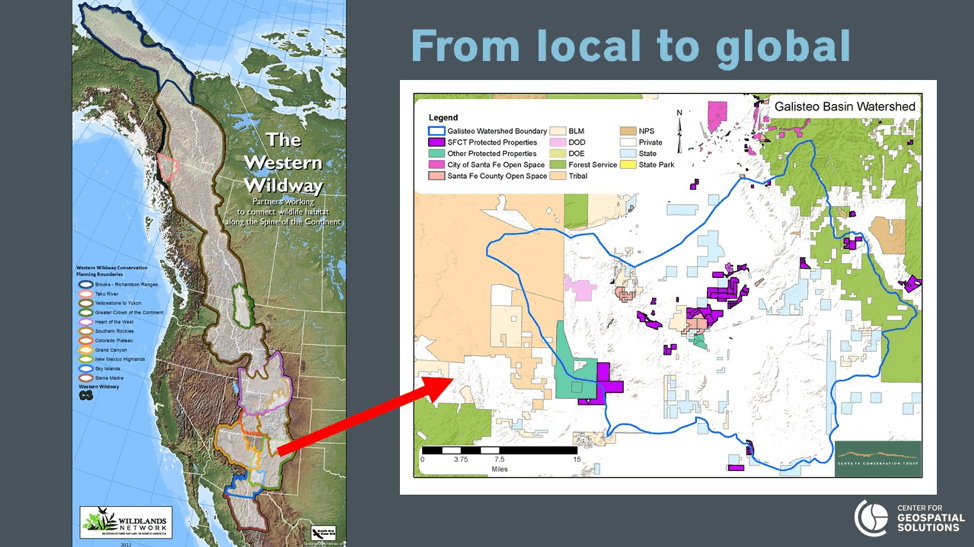

One of the joys of writing this book was the opportunity to seek out and connect with organizations that work in the United States and internationally to pioneer up-and-coming innovations that use GIS and technology to scale our efforts to be more efficient and effective. For example, I tell the story of how the Santa Fe Conservation Trust is working with private landowners in the Galisteo Basin to protect over 18,000 acres of land that provide key wildlife connectivity between the Sandia Mountains and the Sangre de Cristos. (To see how SFCT is leveraging maps and GIS to share their story, be sure to check out this StoryMap). Work like this at the local scale is most powerful when it scales up and nests together at the global level: SFCT’s local conservation around Santa Fe feeds into a much larger trans-national effort to connect wildlife habitat along the Rocky Mountain spine of the continent from Mexico to Canada called the Western Wildway.

The map on the left shows the Western Wildway corridor. The map on the right shows SFCT conserved lands in purple that provide critical connectivity in an area of mostly private land. The Trust continues to add more conservation easements to expand connectivity. This is a great example of how local actions fit into a broader landscape goal that feeds into global conservation targets.

I include a story about how the Grand Canyon Trust is working with tribes in the four corners area to create maps that reflect their indigenous knowledge and perspectives on the lands that are sacred to them to restore protections for Bears Ears. I tell the story of how maps helped to spark and support a grassroots movement to save the Hoback Basin, a key part of the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem in western Wyoming, and how the Highstead Foundation is facilitating landscape conservation in the northeast. And further afield, there are examples on how to use geospatial technology for community engagement by Africa People and Wildlife and the Snow Leopard Conservancy. All of these stories are inspiring and showcase the power of using GIS for conservation.

There are still many challenges to overcome. We need better coordinated efforts to reach America the Beautiful, 30 x 30, and global land protection goals. We must collaborate and partner to work from the same data and maps so we aren’t wasting precious resources. This will result in less duplication of efforts while directing funding and resources to implementation actions on the ground. We’ve come a long way, but we still face a baseline accounting challenge of mapping and tracking what is protected. This applies to public and private lands and includes accounting for lands and waters that are managed for conservation purposes but without conservation status. We need to get the data-driven baseline right so we can prioritize, secure, and manage for a resilient future. This data will help form the maps that will be used to make the case for funding. Let’s all pitch in to make the process inclusive, collaborative, and accessible for communities big and small, indigenous communities, and all partners.

When you know what places need to be protected and managed for conservation, you can create a BOLD vision that strengthens partnerships, is inspiring, engages communities, and is focused on impacts. The solutions to the climate and equity crisis are rooted in place – and we need that perspective to save the places we love. Now is the time to fully embrace this powerful technology to scale conservation and save our planet. We only have one world, time is of the essence.

ABOUT BREECE ROBERTSON: As Director of Partnerships and Strategy for the Center for Geospatial Solutions at the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, Breece builds, connects, and manages the partner ecosystem and supports and guides technology innovation and development. Breece has more than 18 years of experience leading collaborative and strategic initiatives that leverage data-driven platforms, GIS, research, and planning for the park and conservation fields. Breece combines geospatial technology and storytelling to inspire, activate, educate, and engage. During her career at The Trust for Public Land, she led geospatial innovations that supported the protection of 3,000+ places, over 2+ million acres of land, provided park access to over 9 million people, and achieved $74 billion in voter-approved funding for parks and conservation. She is a skilled leader, collaborator, implementer, and creative visionary with a legacy of building award-winning teams and community-driven GIS approaches for strategic conservation and park creation. Esri, the world’s leader in geographic information system (GIS) technology, twice has honored Robertson for innovation in helping communities meet park and conservation goals. In 2006, she was awarded the Esri Special Achievement in GIS award and in 2012, the “Making a Difference” award – a prestigious presidential award.

You can find more information on “Protecting the Places We Love” here. If you are an educator, you can access a free copy of the book through VitalSource. To learn more about Breece’s story visit www.breecerobertson.com

As part of the Network’s Landscape Conservation in Action webinar series, Breece will be presenting a webinar on October 7, 2021–register here to attend the webinar.